I’ve spoken on my YouTube channel a few times about the Baby Boomers and how the hatred toward the generation born in the 40s and 50s has largely earned the collective ire of all others. I considered both of my videos on the subject incredibly gentle, and yet many boomers came out of the woodwork to enthusiastically prove true every stereotype about their generation being cruel, out-of-touch, narcissistic sociopaths. I also used to say that they fail to understand the differences between individuals and groups, but that may not be true, as we shall see. They may simply be tribal.

I talked mostly about the specific actions of the boomers; the response was to either laugh at the misfortune of the young, who will never afford the standard of living they grew up with or to call all others “bad” in some way (lazy, entitled, etc.). The experiences of Gen X/Y childhoods involve specific complaints – things like daycare, divorce, abandonment, inheritance squandering, abuse, etc. These are mostly anecdotes but incredibly common ones. Thus, as I point out, while most boomers are good and did right by their children and parents (and I will talk about good Baby Boomers in the future), a very large cohort with even a slightly elevated percentage of sociopaths will turn anecdotes into common experiences akin to high school. Everyone has a few stories about bad boomers being boomers.

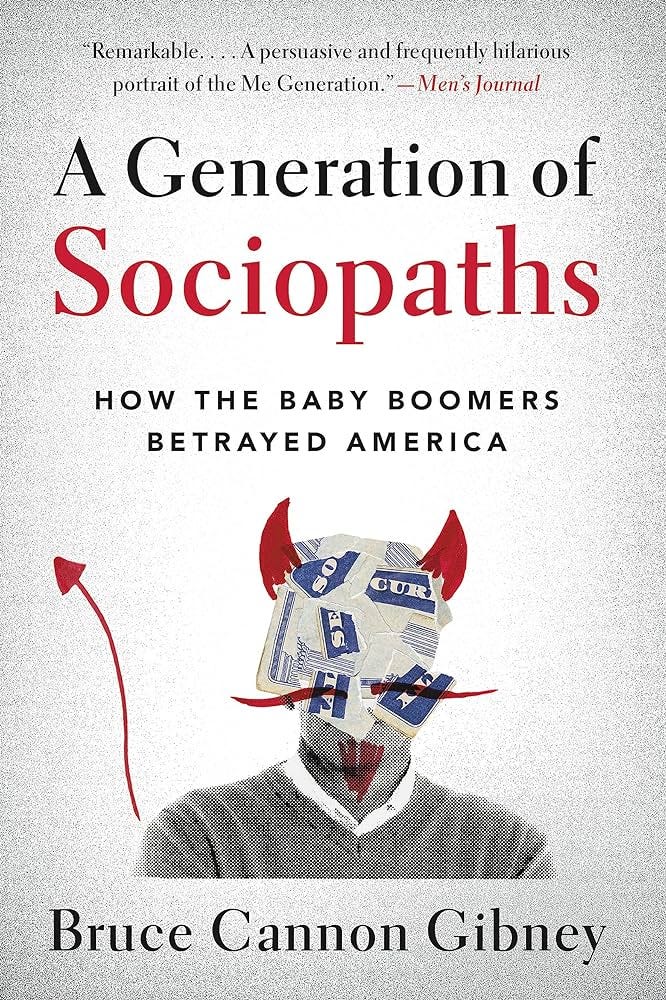

Bruce Cannon Gibney takes a different approach with his book, A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America. His book is all about the macro, backed up by data. The verdict? The Baby Boomers have collectively (or as the emergent behavior of the collective) acted like sociopaths and engaged in what amounts to inter-generational war. They inherited wealth of many sorts, including decades of economic, intellectual, and social investment, and squandered them, breaking all social mores and plundering their birthright while making none of the investments that would have allowed their children to experience the same prosperity and freedom.

The overarching point Gibney makes is that the Baby Boomers acted as a distinct and self-focused cohort politically and socially, realizing De Tocqueville’s warning that democracy would fail when people realize they could vote themselves money (and now, post-Trump, we have also realized the soft tyranny warned of in Democracy in America). Boomers supported subsidies to education when they were in college, then took advantage of usury loans once they were in the investment class and could shove the burden of educational spending onto the young. They supported Social Security reform when they were earners, but now that they are retired, they deserve every dime. They embraced abortion as soon as it was legal, even though it was overwhelmingly disapproved of socially. They embraced environmental legislation when they were experiencing acid rain but are happy to ignore things like global warming, as once that becomes a real problem, they will be dead. They cut inheritance taxes when they were due to inherit, then will ensure their children will inherit nothing. The list goes on.

Gibney’s focus on the macro also revealed one interesting trend I had not before associated with the boomers: evangelicalism. He notes the trend of boomers abandoning mainline protestant churches in early adulthood to either join more liberal protestant denominations or form their own (note: evangelicalism, a product of the Radical Reformation traditions, is liberal in this context, despite many adherents being politically Republican). In our modern world of church-shopping and church-hopping, it is easy to forget that abandoning one’s religion is apostasy, and that takes either a very strong conviction or, as Gibney suggests, a measure of sociopathy. Breaking away from the traditional church requires abandoning beliefs as well as traditions, family, and friends. His point is that modern non-mainline protestant sects are much more self-focused than the old churches, which is why they were attractive to boomers.

Because of the nature of post-boomer Protestantism, I am inclined to agree. The “seeker-focused church” movement is just the current stage of a movement that began in the 1970s: a church for me. My music. My interpretation of scripture. My personal relationship with Christ. And if the pastor sucks, or the music changes? I’ll find a different church. No biggie. The fact that this attitude was satirically warned against in C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters ought to raise eyebrows. It’s interesting to think about because, being born in the 1980s and raised evangelical, I never knew the mainline protestant culture; it had been demolished by the time I was born. It was only being willing to explore tradition that allowed me to see how “me-focused” the evangelical stream was.

While Gibney’s economic and social evaluations are sound and backed by the evidence he presents, there are a few things about the book worth noting.

First, it was written before Donald Trump took office and before Covid hammered home the sociopathy of the boomer generation. Gibney is left-of-center, so it is uncertain how he would interpret the events of 2020 if he were to write the book today. Realities diverged after 2016, and I think he would probably be in the reality where it was correct for the entire economy (minus essential workers like door dash drivers) to be ground to a halt so that baby boomers could lower their risk of dying of a flu. Things like forced vaccinations were for the benefit of boomers, but would he see it that way? Gibney also loves experts, but the medical experts did not perform well in the pandemic at all, to say nothing of the economic experts who have been steering the metaphorical ship into icebergs over the last 20 years.

Second, being a statist, Gibney never uses his copious data to question all his basic assumptions about the modern total state. Things are bad because Baby Boomers used our democratic processes like a collective ATM; he never questions that democracy itself might be bad because it allows the boomers to do what they have done. Schools are bad because boomers ran them poorly and had bad educational legislation; he never questions whether schools were ever that good to begin with (after all, the boomers went to public school) and whether a system that can be so degraded is inherently good. His solution is to raise taxes to fix the system; he doesn’t question the system. That makes him a reformer, not a revolutionary, which is not a bad thing. Prudent reform is preferable to bloody revolution in the vast majority of cases.

Moreover, while his ideas for fixing the mess boomers created are sensible, there is no mechanism for actually achieving them because…well, boomers. The system that allowed boomers to exploit it because of the size and unity of their cohort is incapable of punishing the boomers until they are mostly dead. At that point, why bother? Most of them have bragged about leaving nothing to their children. Raising the inheritance tax, which the author suggests as a possibility, would only punish the generation that came after, if it punishes anyone at all.

His complaints about the US political system boil down to standard liberal talking points such as complaints about low-population states having the same number of senators as New York – which is the point of the Senate. So, while Gibney laments poor civics education, he either lacks some basic knowledge about the purposes of the government’s structure or purposely obfuscates them. If we had suffered more democracy during the boomer years, things would be much worse off now, given the boomers. To the extent he questions the system, it is always to complain that we have too little of it – too little democracy, too little government, too little taxes – while ignoring that the results of boomer politics occurred through that system.

That being said, I still think it is valuable to listen to arguments from people who aren’t politically aligned with yourself. It is good intellectual exercise. When the argument is, “Boomers are sociopathic,” the fact that we do or don’t agree on environmental policy is moot; what matters is what the boomers did versus what they knew. You can point out that college education is a lost cause (a product of boomer faculty) while agreeing that boomers benefited from the system while young and destroyed it to their own benefit while old. Gibney is honest, even when it comes to immigration, which he wouldn’t have tackled in the book were he just a standard partisan leftist.

To that end, the book is a call back to older politics, where people were not afraid to entertain ideas that might be philosophically aligned with the “other side.” Gibney notes that Nixon was to the left of most modern Republicans, and Clinton was more conservative. I remember Milton Friedman, a libertarian economist, suggesting both “cap and trade” pollution credits as well as negative income tax, the equivalent of universal basic income. Because of the way modern politics (led by boomers) work, prudent solutions tend to move out of the political discussion.

Perhaps discussions of prudence were merely a temporary possibility of the 20th century, a respite of a process that is ultimately about the friend/enemy distinction.

What I have learned most from the book, as well as reactions to my own content about Baby Boomers, is that the friend/enemy distinction that boomers see is generational. Friend = boomer. Enemy = everyone else. The unfortunate thing is that the “everyone else” is so sorely divided that even as a minority, the boomers rule because of their cohesiveness in self-interest.

I am an independent artist and musician. You can get my books by joining my Patreon or Ko-Fi, and you can listen to my current music on YouTube or buy my albums at BandCamp.

The insight about Boomers apostatizing in droves out of sociopathic consumerism is a behavior I've noted on the micro level but somehow never applied to generational theory. Thank you.

NB: In my experience, people who've apostatized from Apostolic Churches for worldly reasons like social clout or sex tend to be untrustworthy.

"Schools are bad because boomers ran them poorly and had bad educational legislation; he never questions whether schools were ever that good to begin with (after all, the boomers went to public school) and whether a system that can be so degraded is inherently good. "

CS Lewis points to the education of the Silent and Boomer generation as being degraded from his own. CS Lewis and his generation were probably the last get a serious Western education, itself somewhat degraded by then. (CS Lewis boarding school had problems to put it mildly.) It's a difficult thing to point out to people so sure it was better (and it was to an extent) that they had been carefully trained by the system to believe in the equivalent of communist social engineering. The Founding Fathers in the US at least would have had no idea what to do with them.