I tweeted out a quick bit about Dracula the other day and how it’s easy to miss all the inversions if you approach it as a monster story from the post-protestant mindset rather than a piece about inversion and spiritual warfare.

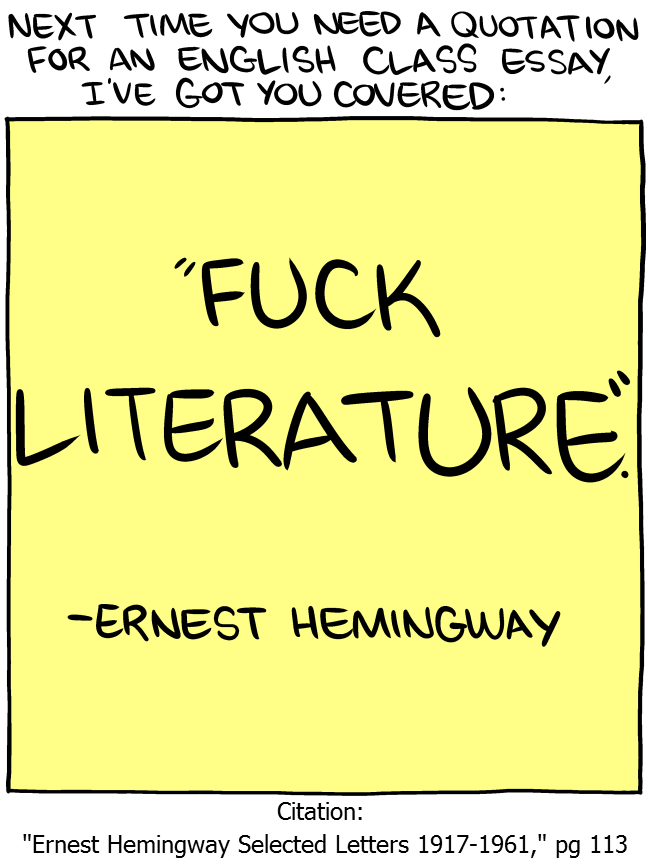

That quickly brought up the fact that books like Dracula are often ignored in literary studies in favor of modernist authors and the American “classics” of the first half of the 20th century. When taken as a whole, what emerges from that collection of books, spearheaded by writers such as Steinbeck, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Joyce, Eliot, and Faulkner, is an overwhelming fascination with nihilism. I am not the first to call such books “misery porn.”

On the one hand, their historical analysis is interesting because they are swimming in the modernist current and thoroughly exhibit the modernist ethos, which is concerned with making new things, creating new aesthetics, and creating better men. That is an optimistic outlook, however bad the outcomes from such a worldview were. On the other hand, most of those books written between the World Wars are also deeply pessimistic and often avoid any kind of optimistic conclusion to conflicts.

These are not tragedies in the dramatic tradition but books with bad endings, where bad things happen and nothing is gained, either materially or morally, by any characters, and those bad things are usually not anyone’s fault. That is not to say they are devoid of moralizing (in fact, they can be heavy-handed), but the classic approach to tragedy in which a noble character suffers because of a vice of moral failing is absent from modernist tales.

Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck, is a classic example that I was forced to read in the 9th grade and was, being but a lad of 14 and barely out of my Ninja Turtles phase, not prepared to fully understand. That’s okay, perhaps, because my teacher didn’t understand it all either. She thought it was tragic how the “Best laid plans of mice and men often go agley” rather than a moral tale about how everyone would be better off without the mentally disabled. Of course, my boomer teacher might have loved the book for that message, that the people who depend on you who are an inconvenience would be better off not existing (forget not that Boomers aborted 1/3 of their children), but if so, she never expressed it.

George constantly complains about his mentally deficient charge, Lenny. All the messages of the final act are telegraphed in the exposition. Lenny kills mice on accident (he’s dangerous!). A man regrets letting another man euthanize his dog. The conclusion precipitates due to Lenny repeating his accident, this time on a human. It is quite farcical when one thinks much about it at all—adult human necks don’t just snap on accident—but the point was to show that the mentally retarded Lenny is always and forever a danger and incumbrance to everyone. The entire world would be better off without him. So, echoing the dog, George murders him by shooting him in the back of the head. Like euthanasia, this is framed as a mercy.

George is not a tragic hero; he is just a man who suffers the misfortune of Lenny, and he suffers no ultimate downfall. In fact, he is (presumably) finally liberated through the act of murder. Lenny isn’t a hero; he’s a force of nature. Curly might be a villain, but so what? George’s real problem is Lenny, or the story would have had a drastically different final act.

It’s not hard, when reading about the political trends of the early 20th century, to see this is a tale that is concerned with eugenics. It accomplishes with artificial emotion a position that doesn’t quite parse in data or real life, which is that killing the disabled is a mercy. This is not far-out for a time in which disabled people were forcibly euthanized, and figures like Margaret Sanger advocated for birth control for eugenic (and racist) reasons. Lenny’s life is drawn so that the reader will ponder, “Wouldn’t it be better if he had never existed?” Dark.

Steinbeck is by no means the only culprit. In the same year, I had to read Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemmingway, another misery porn piece, and the book also has the distinction of being the most boring novel I have ever read. At only 33,000 words, that is saying something. Old man goes fishing, catches a big fish, and sharks eat it. He gains nothing. The struggles of fishing. The end.

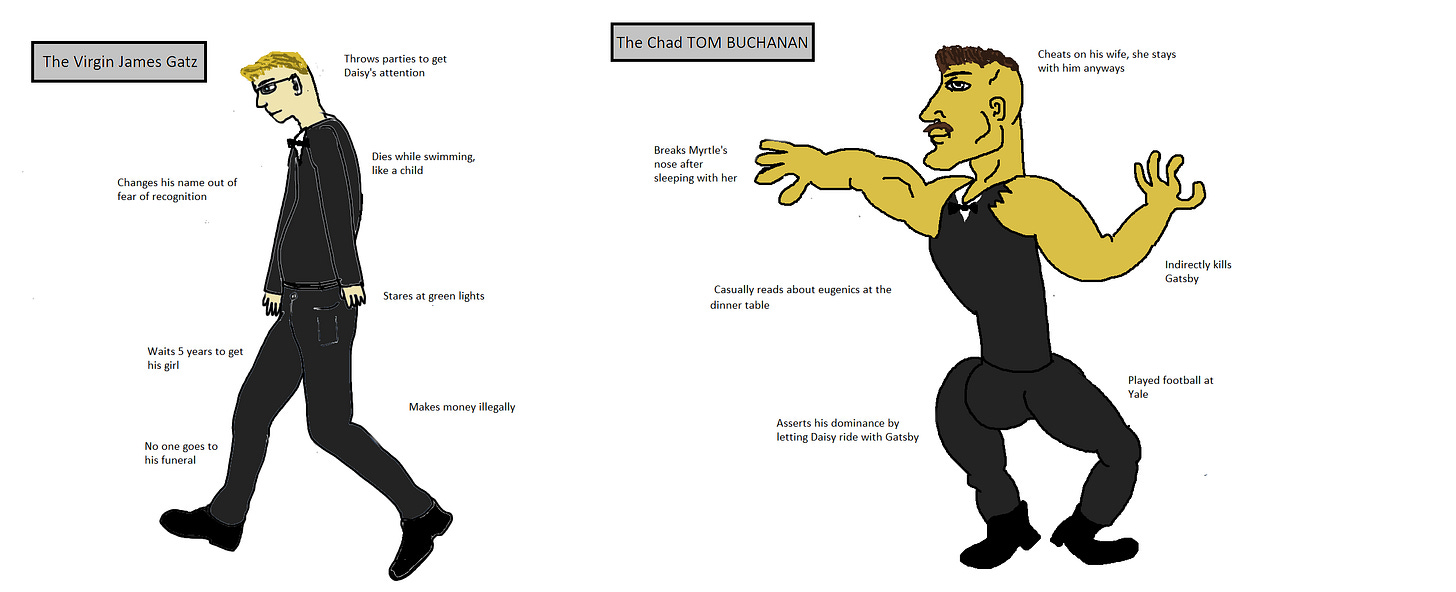

Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is probably the most overrated work from my high school reading list, notably because of its random, nihilistic ending. Gatsby gets humiliated after getting the woman he wants (who is married now), gets told to drive the dude’s wife home, and they accidentally run a woman over. Gatsby is shot in a case of mistaken identity. The narrator looks at the boats paddling upstream. The river is like time, you know? And Gatsby is like… A really sad pathetic guy who got dumped for being poor. When you know Fitzgerald’s life, it’s hard not to read the novel as anything other than a metaphorical virgin walker seething about the Chads in his life and the women who wouldn’t give him the time of day.

I love 1984 and its message, but we have to be honest. It is misery porn. There is no overthrowing the government and the characters were stupid to even think it was a possibility. Everybody is too passive, stupid, or dependant upon the state for all the motivations of the characters to matter at all. Even worse, Winston loses everything and then, through obscene torture, gets broken so that he, too, loves the state and no longer loves Julia.

Even the classic To Kill a Mockingbird is precariously close to misery porn. The innocent man gets locked up because people in the South are just super, duper racist, and then he is shot dead. The white trash perpetrator of the whole affair gets his comeuppance at the end, showing that Harper Lee knew the need to provide the audience a sense of catharsis—at least justice can be cosmic if it cannot be trusted to men.

These books aren’t bad per se. In fact, many are great examples of the craft. The prose is good. Sometimes damn good. The characters are, at times, sharp and resonant. The books are just pointing to nothing or unsavory political ideas that most of the literati would prefer to, in the 21st century, distance themselves from, so they pretend the themes aren’t even there.

I balked at age sixteen when being forced to read Jane Austen, but I think now, though I might still find her uninteresting, the stories were at least witty and had good endings. They were downright wholesome compared to Steinbeck.

Keep in mind this is what the state forces children to read. No wonder so many people graduate and only read Twitter posts and video descriptions on YouTube afterward. Everyone in the 1990s complained about Cliff’s Notes, but can you blame them? We had to read this stuff and then divine what our teachers wanted us to write in our essays to get full marks. The notes didn’t just give you the plot points; they told you what answers the teacher wanted from your “thoughtful” essay.

That thoughtfulness and careful consideration was usually the “historical context” discussed in the notes, things like the Great Depression (the economic period, not what the student feels reading Steinbeck), the Roaring 20s (the most important part of the Great Gatsby for librarians unable to detect male pathos), or Orwell’s disillusionment with the Soviet state (rather than the message that 1984 was our destiny, too). Most 14-year-olds are not going to get political themes or meta-analyses, and more importantly, they don’t care. Cliff and Spark were the heroes of the 1990s.

There is a deeper debate here about what a literature course ought to be, and I’m going to sidestep that to merely point out what the result of the curriculum of the late 20th century produced: a population that hated “literature” and saw no reason to seek it out as adults. The publishing industry didn’t help things, but that is also another story.

I’m sure there are many other misery porn books from the first half of the 20th century you could point out, some explicitly pointed toward children (The Giving Tree, perhaps?). Link them in the comments.

Just as a quick aside, I edited this post because I quoted the end of Gatsby incorrectly and left out details, then remembered them after I posted the article. Just goes to show how random the resolution was, I suppose, that I didn’t remember it.

I am an independent artist and musician. You can get my books by joining my Patreon or Ko-Fi, and you can listen to my current music on YouTube or buy my albums at BandCamp.

I maintain that there is no more effective way of dissuading a population from reading recreationally than the tactics American public school system employs. Choose bad (poorly written or uninteresting or arduous or overrated) books, determine the amount that can be read in a week (usually a chapter or two), make students sit and listen to their retarded classmates struggle through an agonizing five minutes "read out loud" session in class, get a quiz or test on specific and unmemorable details...and you've added a pertinant point: choose nihilistic books. And, because this is done under the guise of beneficent "teaching kids to love reading", nobody can stop the process from happening to generation after generation, as we collectively pretend that it's appropriate.

I was lucky that I was into Star Wars books. Not high brow, but they kept my flame alive while I watched almost all of my classmates disassociate reading from fun.

Ugh, I learned to sniff out misery porn in kids books from the time I was a teen. Bridge to Terebithia, The Moves Make the Man, Walk Two Moons, and on it goes. I learned to associate that jokey, funny narrator voice with what I called "the sting in the tail", where you get to the end of the book and the protagonist stands on the edge of the cliff and looks at the remains of the bus where her mother died. Oh yeah, grind the noses of the young in it. The only break in this misery train was Holes, which does have the jokey, funny narrative, but it actually tells a good, uplifting story where the heroes are rewarded and the villains are punished. I eventually gave up on modern kids books and went back to older classics, of which there are plenty.